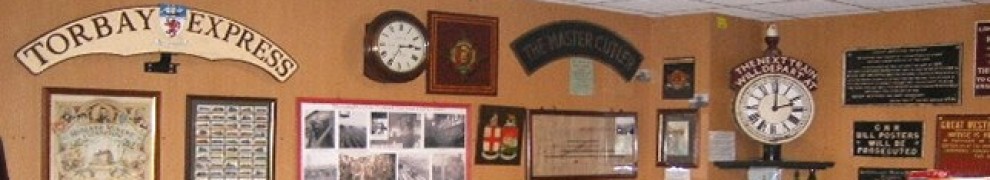

153 – Chasewater Railway Museum Bits & Pieces from Chasewater News Dec 1992 – Part 3

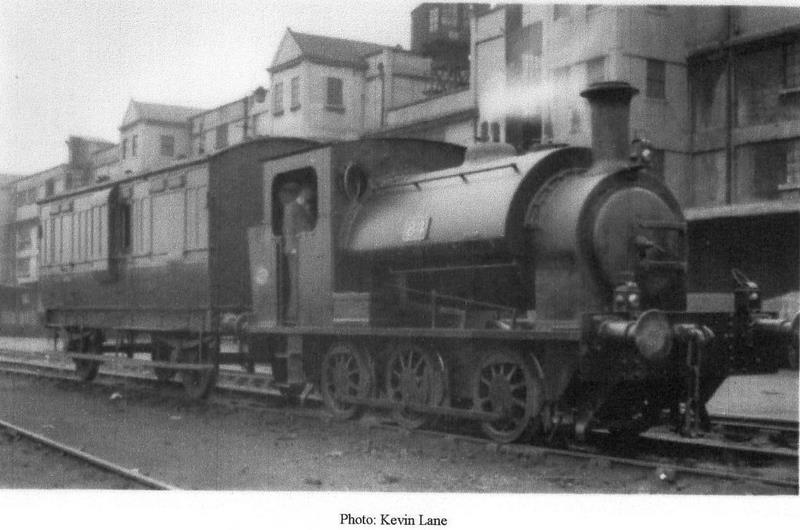

This small gauge loco, with Isle of Man connections, used to make fairly regular visits to Chasewater , this picture and the one at the end of this post have absolutely nothing to do with ‘Carriage & Wagon News’, but they were in the magazine and I just wanted to use them!

Carriage & Wagon News

A sad note to start with is that at the last Board meeting, Dave Whittle stood down as C & W director. There are many problems concerning the stock, and with Dave’s other duties including our very successful rallies which Dave helped to arange, the work load was too much.

Maryport & Carlisle six-wheel coach – Work has begun on the far side of the coach where a canopy has kept dry the rotting window frames and doors. These will be treated and painted, but the stock of plywood has completely dried up with no funds for further supplies.

Midland four-wheel passenger brake – Tony Wheeler has undercoated the exposed main end timbers to protect against the weather until plywood sheeting becomes available.

Manchester, Sheffield & Lincoln six-wheel coach – This vehicle has remained sheeted up but will shortly be needed for the local colliery railway history information centre when the Southern brake van goes to Chatham in 18 months time.

16 ton Great Western Toad – Tony Wheeler has re-painted the superstructure of this vehicle which looks good on our permanent way train. Unfortunately Tony could not gain permission to paint the mess van.

CCCC brake van – Unfortunately due to other projects, Keith Poynter has not had much time to work on his pride and joy. Photographs from our museum showing this vehicle in service on local lines will soon prove their value during the restoration.

Great Eastern six wheel passenger brake – But for a missing door and one or two small panels, the whole of one side has been completed – albeit in four different colours. The age of this coach has now been established in the preserved carriage handbook as being 1894, and being numbered 44, ties in with other coach dates. So 1994 will be its centenary year.

Midland box van – Tony Wheeler has begun work on the exterior paintwork of this vehicle, scraping and painting.

Southern brake van – Work on re-painting this vehicle has been suspended for the time being at the request of its owner. Tarpaulins have been put over the roof, and a pot-bellied stove fitted inside in an attempt to dry the inside out so that a start can be made on our colliery history information display.

Museum Coach – Although we have just suffered the worst November rain for ten years, Steve and Keith have almost completed the re-roofing (in a new tar-based material) of the LNWR ‘James’ coach. The inside has been scraped and painted, with the help of the Duffs, to house our Santa’s Grotto before the relic collection is moved back in.

Gloucester trailer E56301 – Having remained in use throughout the year, this vehicle has now finally been withdrawn from service and will not run on the Santa Specials.

Wickham trailer E56171 – This coach has also been in use all year, and now that the loco is attached to the northern end of the train, it is the only one with the driving cab at the correct end for the guard. A recent trip by CLR members to Tyseley produced an amazing amount of spare parts for our DMUs, bought at scrap prices. As a result, this vehicle has benefited to the rune of a new set of batteries, a new heater and a new heater control in readiness for the Santa trains.

Derby centre car W59444 – This coach has also received a new set of batteries in the last few weeks and will run in service for the first time on the Santa trains. Although still in undercoat the coach looks very impressive, possibly due to its being around 7½ft longer than our driving trailers and certainly helps fill the platform.

Wickham power car E50416 – Work has continued on the refurbishment of this vehicle which will also be receiving a new set of batteries (four coach sets in all were obtained). A lot remains to be done to the interior and some broken windows renewed before it can enter service.

Dave Borthwick

Beyer Peacock Anglesey inside shed with McClean. Cannock Chase Colliery Company

154 – Chasewater Railway Museum Bits & Pieces

From Chasewater News Dec 1992 – Part 4

Cannock Chase Colliery Company

Transport Development – The Formative Years

Mike Wood

Cannock Chase prior to 1840 was an expanse of barren, desolate heathland with no centres of population and without developed rail, road or water networks – on of the last great wildernesses of England. The villages of Chasetown and Chase Terrace did not yet exist and were twenty years into the future. Its few inhabitants made a living from the land selling agricultural produce at market in Cannock or extracting coal from shallow bell pits or drift mines. There was not only coal on the Chase but also ironstone. Local opencasters had been aware of its presence for many years but made no use of it as the smelting of iron required organisation and equipment well beyond their primitive means. For the mineral resources of Cannock Chase to be exploited to the full, big business had to take a hand. In the form of Henry William Paget, landowner and Marquis of Anglesey, and John Robinson McClean, civil engineer, big business was just around the corner.

The Marquis of Anglesey, whose estate encompassed almost entirely what was to become the Cannock Chase Coalfield, did not begin exploitation of the mineral wealth on his lands until the mid 1840s. By this time, coal had superseded water as the new power base of the industrial revolution with the increasing use of steam driven machinery in factories and for producing iron. The success of Stephenson’s ‘Rocket’ at Rainhill in 1829 had also led to the widespread adoption of steam traction on the new fast-growing railway network. The comparative late development of the Chase as a coal producing area is almost certainly attributable to the absence of a satisfactory transportation network of roads, railways or canals.

The first canal to enter the region was not completed until 1797, when the Wyrley & Essington completed its north easterly course from Wolverhampton to Huddlesford Junction near Fradley where it joined the Trent & Mersey Canal. In connection with this W&E scheme, a large feeder reservoir was created in 1798 by damming Crane Brook at a point one mile north of Watling Street between what are now the villages of Brownhills West and Chasetown. Norton Pool, as it became known as, was constructed as a storage facility in connection with maintenance of water levels on the main W&E canal. Access from reservoir to canal was via a narrow drain-off channel of approximately 1¼ miles in length to Ogley along the exact course of what eventually became the Anglesey Branch of the W&E or ‘Curly Wyrley’ as it was known locally.

By 1840 the national canal network comprised over 4,000 miles of navigable waterways providing a means of high capacity, low cost transportation,

It is certain that the presence of a new waterway crossing the southern boundaries of his estate plus imminent construction of the South Staffordshire Railway, due to be opened in 1849, and padding by in the same area as the canal, finally encouraged the Marquis to exploit his underground wealth.

In 1845 the Marquis directed that shafts be sunk at Uxbridge, Hammerwich and Four Mounts on the south eastern shores of Norton Pool, 1½ miles north of the W&E canal and the proposed South Staffs Railway.

This photograph was taken from the same spot as the previous one – but after the M6 Toll road came into being! The old bridge in Wharf Lane can be seen through the newer one.

The canal company built its Anglesey Branch in 1850 by enlarging its drain-off channel from a main line junction at Ogley. This branch terminated at Anglesey Basin, a few yards south of Norton Pool where facilities included stables, offices, coal loading chutes and gantries, plus a railway interchange which opened in 1858. Deep moorings accommodated the endless stream of high capacity canal boats which were to pour their black wealth south down the Birmingham Canal Navigation to fire the industries of Birmingham and the Black Country.